Feb 24 (Reuters) – A record number of women and minorities hold seats this year on the boards of the Federal Reserve’s 12 regional banks, providing perhaps the most diverse range of input ever as those banks’ presidents – alongside Fed governors in Washington – wrestle with how to slow inflation without tanking the economy.

Fed bank directors generally stay out of the limelight, but many U.S. central bankers view them as a critical resource. Indeed, some argue prospects for a best-case outcome to their policy-tightening campaign are heightened by the advice from such a wide spectrum of voices.

“I think the probabilities are far higher of achieving that gentle transition, that smoother transition,” San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly told Reuters in an interview.

Daly, her 11 bank president peers and the six current members of the Fed Board face some of the toughest decisions in their central banking careers in the months ahead.

After jacking up interest rates by the most since the 1980s last year to combat too-high inflation, they now want to find the right stopping point – a level of borrowing costs that can slow a surprisingly resilient economy still being reshaped by the COVID-19 pandemic without causing extensive harm in the form of large-scale job losses.

To find it, they’ll be advised by a small army of PhD economists across the Fed system.

They will also draw on what Fed Chair Jerome Powell called earlier this month a “haul” of anecdotal information on the real economy from the regional Fed banks that dot the country.

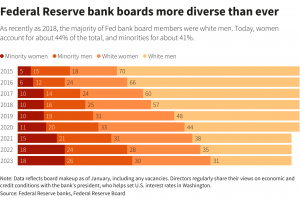

Central to getting that information, Fed bank presidents say, are their regular huddles with their boards, panels that until as recently as 2018 had largely been cut from the same cloth: bankers and business leaders, most of them white men.

Years of efforts by Fed leadership, as well as pressure from lawmakers and community groups, have changed the picture.

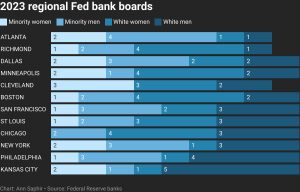

This year, of the 108 spots on the 12 Fed bank boards, 44% are filled by women, and 41% by people of color, a review of the data shows.

By comparison, despite a sharp increase in the appointment of minority directors since the upheavals over racial justice in 2020, the average board at publicly traded U.S. companies is still just 26% women, and 19% minority, according to an analysis by Cornell University professor Scott Yonker.

UNSOLICITED INSIGHT

Nine directors oversee each Fed bank’s operations, three of whom are bankers. The six that are not bankers choose a new president when the job opens up.

In addition to picking the regional bank leaders, directors “always provide important insight into how monetary policy impacts the economy,” Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic told Reuters. “As we quickly tighten policy to address high inflation, their diverse perspectives help us understand how our actions affect Americans living in a very broad range of circumstances and inform how we can best calibrate policy to avoid unnecessary dislocation.”

Bostic’s own board, in fact, this year marked a milestone for the Fed system. In a first, the Atlanta Fed board now has a Black woman among the ranks of its commercial banker directors, long the least diverse of the three director classes comprising the boards.

The directors are constantly offering up recommendations of people and businesses to talk to about policy impacts and the economic outlook, according to Daly and others.

“We use that network to really learn,” said Daly, whose district stretches from Alaska and Hawaii to Idaho and Arizona. “And I think it absolutely increases our chances of doing this well.”

After what Daly and her colleagues now acknowledge was a late start to battling high inflation, the Fed began raising rates last March and ramped up quickly. She and her colleagues worried about the impact of higher borrowing costs on minority communities, which tend to lose jobs faster in economic slowdowns than richer or white Americans.

But her directors and their contacts told her a different story, she said.

“Again and again, without solicitation, they just tell me inflation is really hurting the people we serve, especially low- and moderate-income people, and it’s informed how I think about policy, and how I think about what is optimal for the country,” Daly said.

Other colleagues feel similarly.

“They give us context to talk to other people that open up our thinking about what these communities are facing,” Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker said of his board. “And I find that incredibly valuable as a policymaker.”

‘HIT THAT SWEET SPOT’

Fed policymakers have undergone their own transformation in recent years, with five people of color now among the Fed’s 18 current policymakers.

Still, a majority of the Fed’s economists are white men, as are its top two monetary policymakers: Powell and New York Fed President John Williams.

And despite progress on diversifying bank boards by gender and ethnicity, critics say directors are still drawn too heavily from big business and finance and do not adequately represent nonprofit organizations and labor, among others.

Senator Bob Menendez voted against Powell’s 2022 confirmation to a second term to register his disappointment in the Fed’s diversity. He is urging President Joe Biden to pick a Latino to succeed Lael Brainard, who last week vacated the Fed’s vice chair role for a job at the White House.

“We have repeatedly seen through economic crises and recessions that the brunt of the impact falls on communities that were already struggling – those are minority communities,” Menendez told Reuters, a point that Fed policymakers themselves frequently make as well.

Hispanics and Latinos, Menendez notes, are a fast-growing segment of the population but are underrepresented at the Fed at all levels, including on Fed bank boards. “Decision makers need that first-hand perspective of the disproportionate impact their decisions may very well have,” Menendez said.

Fed policymakers say they value diversity on their boards for many reasons, including research showing that more diverse groups make better decisions, and the need for accountability to and credibility with the American public.

This year, those directors may play a more important role than ever in shaping policy, says Kaleb Nygaard, research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania.

A diverse slate of directors “increases the odds that the Fed will be more in touch with what’s happening on the ground” he said, so that it can “hit that sweet spot – what’s the soonest that we can stop being overly tight and yet still keep inflation under control?”