WASHINGTON, (Reuters) – The Biden administration’s new tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles and other strategic sectors aim to protect the future of U.S. manufacturing, but they will likely accelerate a shift of Chinese production to Mexico, Vietnam and elsewhere to avoid them.

U.S. officials and trade experts say that without strong efforts to cut off transshipped or lightly processed Chinese goods from Mexico and other countries, China’s underpriced excess production will still find its way into U.S. markets.

“The new tariffs might keep out imports from China but it is likely that much of those imports could be rerouted through countries not subject to the tariffs,” said Eswar Prasad, trade policy professor at Cornell University and a former China director at the International Monetary Fund.

Mexico and Vietnam, in particular, have benefited from escalating U.S.-China trade tensions due to their lower costs and proximity, Prasad said, adding that they both need to avoid Washington’s “ire” while reaping new manufacturing investments.

Mexico, for one, has overtaken China as the top source of imports into the U.S., with more than $115 billion of goods originating from there in the first three months of 2024 versus less than $100 billion from China.

With that surge, concerns have grown about Mexico becoming a transshipment hub for Chinese goods to skirt U.S. tariffs, due to increasing U.S. imports of steel products from Mexico and Chinese EV maker BYD scouting out locations for a Mexican factory that could potentially supply the U.S. market. Reuters reported last month that U.S. officials have pressured Mexico to refuse investment incentives to Chinese automakers.

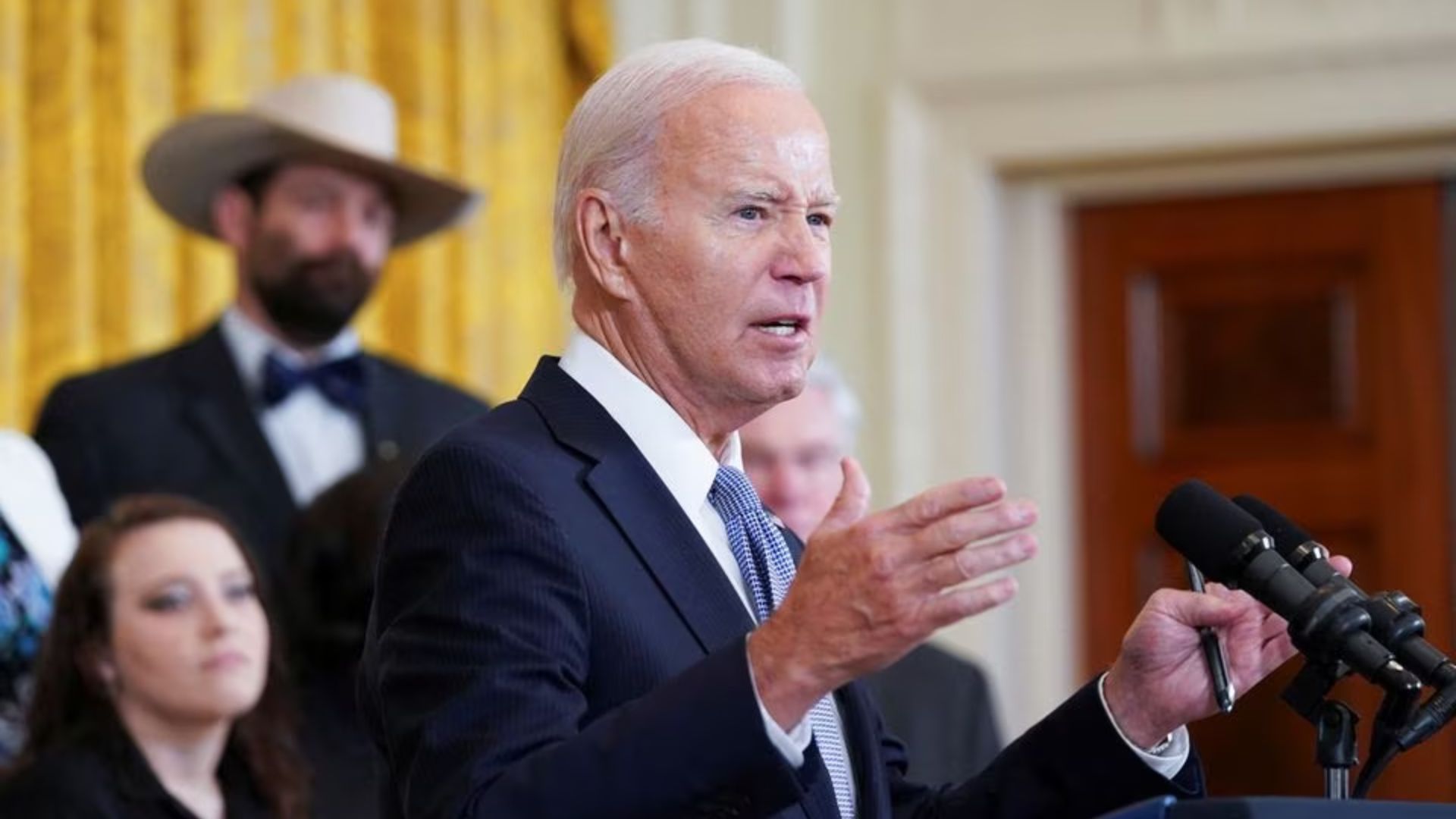

Punitive duties on Chinese EVs will soon be quadrupled to more than 100% under President Joe Biden’s new tariff hikes on high-technology imports from China. The action also includes a doubling of duties on semiconductors and solar cells to 50% this year and new 25% tariffs on Chinese critical battery minerals, Chinese graphite and EV battery magnets over the next two years.

The tariffs are designed to protect new domestic manufacturing sectors that the Biden administration is trying to develop with hundreds of billions of dollars in tax incentives and grants.

‘FACT PATTERN’ TROUBLING

U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai told reporters she was concerned about Mexico’s trade relationship with China and to “stay tuned” on future separate efforts to head off tariff evasion problems.

“The fact pattern that’s developing is one that is of serious concern to us, and that at USTR, we are looking at all of our tools to see how we can address the problem,” Tai said.

Mexico benefits from largely zero U.S. tariffs under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement on trade, while the U.S. Commerce Department is considering granting Vietnam “market economy” status, which would reduce anti-dumping duties on Vietnamese imports.

Another USTR official, senior adviser Cara Morrow, told Reuters in an interview prior to the China tariff announcement that the trade agency has been engaging with Mexican counterparts about ways to reduce the rising transshipment of Chinese steel and aluminum through Mexico.

Biden’s move increases the “Section 301” duties on steel to 25% from 7.5%, but there are also 25% national security tariffs and triple-digit anti-dumping and anti-subsidy duties on many Chinese steel products.

U.S. officials have made it clear to Mexico that the USMCA was intended to promote North American integration and competitiveness, “not to provide a back door to China,” Morrow said, adding that both sides want to prevent it from becoming an issue in an expected 2026 review of the trade deal.

Under the pact put into force in July 2020, the three countries could seek to renegotiate or terminate USMCA after six years.

USTR is discussing Mexico’s anti-dumping duties on steel and aluminum and better monitoring imports and exports of the metals and other steps in “difficult” negotiations, but Mexican officials also see Chinese overproduction as a threat to their own economy, Morrow said.

Biden’s action also could put more pressure on Europe by diverting Chinese excess production of EVs, solar products, batteries and steel to their shores, where EU trade protections are generally lower.

Trying to block Chinese excess production “is like squeezing a balloon. It shrinks in one place and pops out in another,” said William Reinsch, a trade expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

Reporting by David Lawder in Washington Editing by Dan Burns and Matthew Lewis