By Nick Carey and Christoph Steitz

Summary

WOERT, Germany, March 22 (Reuters) – The shift to electric cars may pose an existential threat to suppliers of combustion engines but for auto parts firms such as TE Connectivity (TEL.N) the challenge is keeping up with demand.

It makes the connectors that link miles of cables in cars to all things electrical, from sensors to fuel injection systems to infotainment – and if there’s anything the cars of an electric era will need, it’s larger and ever more complex connectors.

And that’s why it’s on the lookout for acquisitions or partnerships to keep expanding its auto business, Chief Executive Terrence Curtin told Reuters: “We’re going to continue to add capacity.”

As legacy auto parts suppliers figure out if and when to sell combustion engine businesses or buy EV parts makers, TE and rivals in the connectors or sensors businesses such as Sensata Technologies (ST.N), Amphenol Corp (APH.N) and Molex are looking to supply higher-value components and do more development work with carmakers going through a massive transition.

Auto parts account for over 40% of TE’s $15 billion in revenue, making it one the biggest car suppliers most people have never heard of. Its $43 billion market value is far bigger than Nissan and Renault (RENA.PA) combined – and more than three times heavyweight supplier Continental (CONG.DE).

EUROPEAN DEMAND EXPLOSION

TE’s Curtin said car parts suppliers and automakers alike had been caught out by an explosion in demand for EVs in Europe over the past two years – and with everyone playing catch-up TE’s new facility was running at double its planned production.

While a global shortage of semiconductors has hit overall car production, Curtin said automakers have been using the chips they do have to prioritise EVs over fossil fuel vehicles – putting ever more strain on suppliers such as TE.

The challenge TE faces is getting the timing and scale of its expansion right, given the EV transition and shift to self-driving cars could run into speed bumps, such as an end to subsidies or safety concerns, Curtin said.

Because for TE, electrification means going bigger.

The far greater power needed by EVs means TE must develop larger and more complex components to handle the extra current, without causing fires.

TE’s conventional parts have up to five components but its newer EV parts have up to 50 components. The supplier also now buys tonnes of aluminium, which is lighter and cheaper than copper, to make up portions of those larger parts.

In the older part of the Woert factory, machines spit out 16 connectors for fossil fuel cars a second. In the new building, more complex and costly machines, some supplied by Germany’s Manz (M5ZG.DE), crank out larger copper connectors with welded alloy springs for EV charge ports at a far slower pace.

TE also makes a large connector here that sits atop an EV battery module – an EV has up to 12 modules – and serves as its brain, measuring each battery cell’s performance while a tiny semiconductor measures their temperature.

The new facility in Woert can make 2 million such connectors a year but demand continues to soar.

“We’re going to need more,” said Matthias Lechner, TE’s head of Europe, Middle East and Africa, adding that TE planned to manufacture more at a plant in Hungary and elsewhere.

Lechner, who describes TE as “humble and hidden”, says its connectors can reduce EV charging time by 10 minutes, an edge carmakers can sell to consumers.

CEO Curtin says EVs and self-driving cars will double the value of the parts TE supplies from about $70 now for the average fossil fuel car. That means the payoff could be huge.

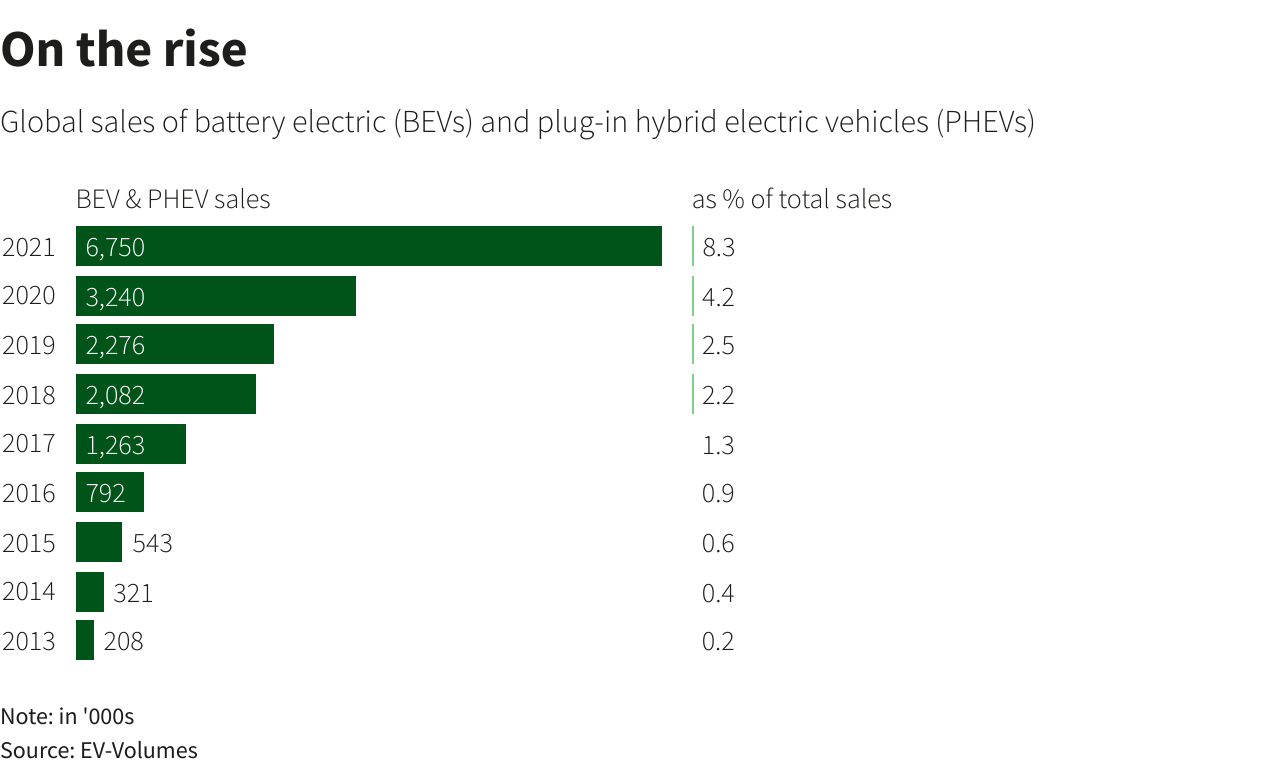

EVs almost doubled their global share of vehicle sales to 6% in 2021, according to research group JATO Dynamics, and that share is only set to rise.

Europe’s auto supplier market will grow to 330 billion euros ($359 billion) in 2030 from 216 billion now, driven by software, EVs and electronics, McKinsey estimates, as firms tackle chip bottlenecks and cost pressure while investing in growth.

“We’re observing a double transformation,” McKinsey partner Timo Moeller said.

TE’s Woert site employs 2,200 people and is adding more engineers and technicians, as well as different machines to make connectors for data in self-driving cars – because unlike EV parts, tiny connections are better for moving data.

TE has three auto parts factories in Germany and another five across Europe. Worldwide, it has 29 factories dedicated to its automotive business.

Morningstar’s Kerwin said TE faces the same risks as others in a cyclical business such as the auto industry.

But he said TE had a “sticky” relationship with customers and has embedded engineers with carmakers to develop products for vehicles in an electric age.

“The writing is on the wall that you have to play into electrification if you want to succeed,” Kerwin said.

($1 = 0.9194 euros)