BOSTON, (Reuters) – Massachusetts has become the latest front in a years-long battle in the United States over whether ride-share drivers for Uber and Lyft should be treated as independent contractors or employees entitled to benefits and wage protections.

The state’s top court is set to hear arguments on Monday over whether to let dueling ballot measures go before voters in November that would redefine the relationship between app-based drivers and companies like Uber, Lyft, Instacart and DoorDash whose businesses help fuel the gig worker economy.

An industry-backed proposal would treat app-based drivers for these companies as independent contractors entitled to some new benefits but would make clear they are not employees. A labor-backed proposal would let Uber and Lyft drivers unionize.

Uber and Lyft also are preparing to face trial on May 13 in a civil lawsuit filed in 2020 by Maura Healey, who was the state’s attorney general at the time and is now its Democratic governor. Massachusetts accuses the companies of unlawfully classifying their drivers as contractors to avoid treating them as employees entitled to a minimum wage, overtime and earned sick time.

Should the industry fail in court and at the ballot box, Uber and Lyft face the prospect of a sweeping overhaul of their business model. Uber’s lawyers said in court papers such a change could force it to cut or end service in Massachusetts.

A victory for the companies in a state with some of the most employee-friendly laws could embolden them in other states, according to labor activists.

“In Massachusetts, the eyes of the country are going to be on us this year – and in November in particular – because this is ground zero for this fight,” Shannon Liss-Riordan, a lawyer who has pursued cases against Uber and Lyft nationwide, said at an event on Tuesday concerning the ballot questions.

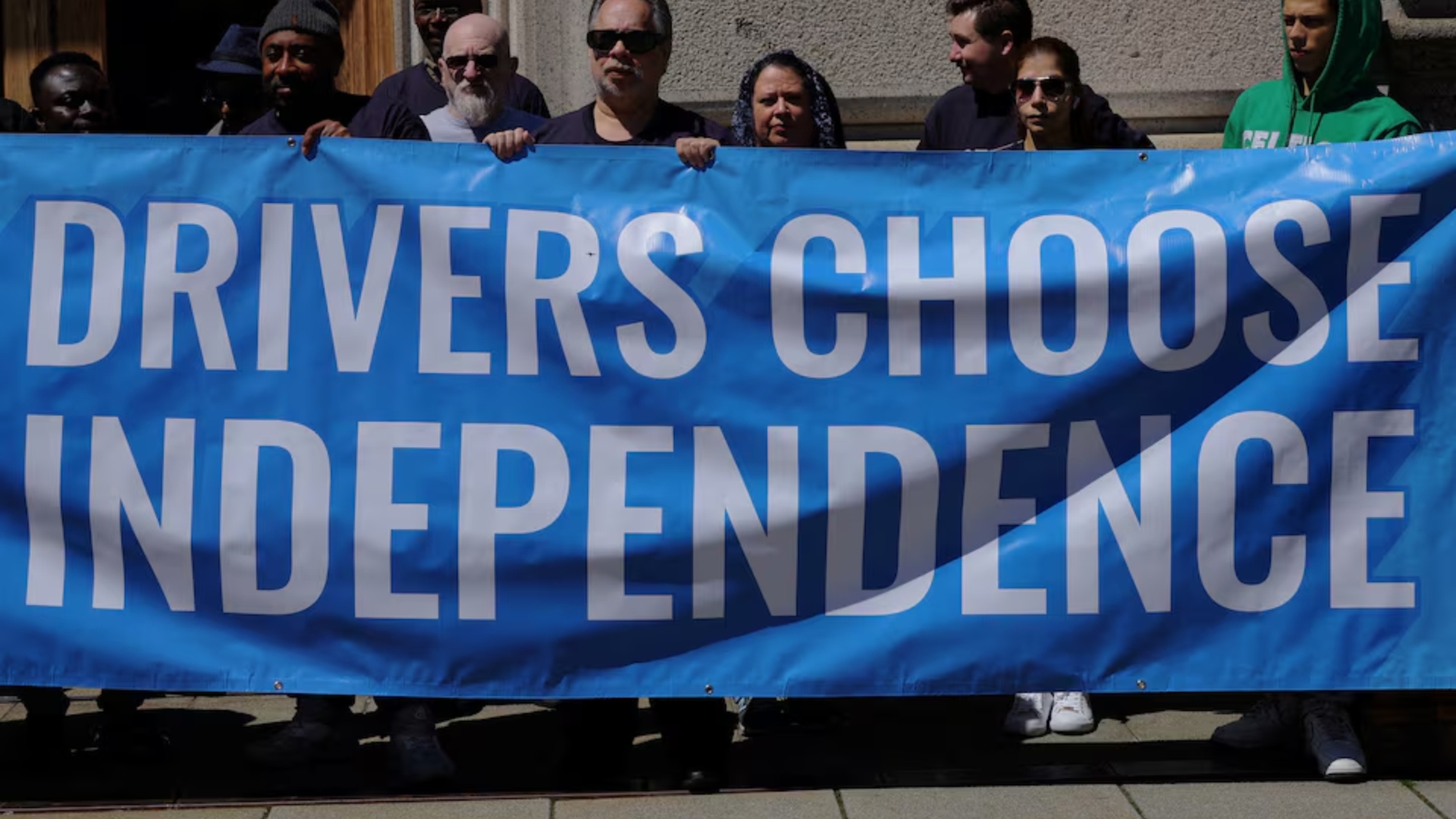

Uber and Lyft have defended against claims that their drivers should be classified as employees because the companies have significant control over working conditions. The flexibility of gig work and the ability of drivers to work for competing apps are hallmarks of independent contracting, according to the companies and their allies.

THE COST OF EMPLOYEES

Employees can cost companies up to 30% more than independent contractors, according to various studies. By not classifying their drivers as employees, Uber and Lyft avoided paying over a 10-year period $266.4 million into workers’ compensation, unemployment insurance and paid family medical leave in Massachusetts, the state’s Democratic auditor said in a report released on Tuesday.

In a $200 million campaign in 2020, Uber, Lyft and others convinced California voters to pass a measure similar to the one backed by the companies in Massachusetts, solidifying drivers as independent contractors with some benefits. Litigation challenging that measure is ongoing.

Fights over the rights of drivers have played out elsewhere. In New York, for example, Uber and Lyft in November struck a $328 million deal with the state’s Democratic attorney general to resolve claims that they cheated their workers out of pay.

The companies in that settlement agreed to institute a minimum “earnings floor” and paid sick leave, akin to the industry-backed proposal in Massachusetts.

Uber, Lyft, DoorDash and Instacart have provided millions of dollars to an industry-backed ballot question committee called Flexibility and Benefits for Massachusetts Drivers to support proposed state ballot measures that would keep app-based drivers as contractors but establish an earnings floor equal to 120% of the state’s minimum wage, or $18 an hour in 2023 before tips. Drivers also would receive healthcare stipends, occupational accident insurance and paid sick time under these proposals.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court blocked a ballot measure similar to the current industry-backed one from going before voters in 2022. To hedge its bets, Flexibility and Benefits for Massachusetts Drivers is gathering signatures for five different versions of the current ballot question, only one of which would be put before voters on Nov. 5.

“Our ballot question will secure all of these things for drivers while allowing them to maintain the minute-by-minute flexibility they cherish in demand,” Conor Yunits, a spokesperson for the ballot committee, said at the Tuesday event.

Reporting by Nate Raymond in Boston, Editing by Alexia Garamfalvi and Will Dunham